Isentropic process

In thermodynamics, an isentropic process or isoentropic process (ισον = "equal" (Greek); εντροπία entropy = "disorder"(Greek)) is one in which for purposes of engineering analysis and calculation, one may assume that the process takes place from initiation to completion without an increase or decrease in the entropy of the system, i.e., the entropy of the system remains constant.[1][2] It can be proven that any reversible adiabatic process is an isentropic process.

Contents |

Background

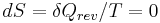

The Second law of thermodynamics states that,

where  is the amount of energy the system gains by heating,

is the amount of energy the system gains by heating,  is the temperature of the system, and

is the temperature of the system, and  is the change in entropy. The equal sign will hold for a reversible process. For a reversible isentropic process, there is no transfer of heat energy and therefore the process is also adiabatic. For an irreversible process, the entropy will increase. Hence removal of heat from the system (cooling) is necessary to maintain a constant internal entropy for an irreversible process in order to make it isentropic. Thus an irreversible isentropic process is not adiabatic.

is the change in entropy. The equal sign will hold for a reversible process. For a reversible isentropic process, there is no transfer of heat energy and therefore the process is also adiabatic. For an irreversible process, the entropy will increase. Hence removal of heat from the system (cooling) is necessary to maintain a constant internal entropy for an irreversible process in order to make it isentropic. Thus an irreversible isentropic process is not adiabatic.

For reversible processes, an isentropic transformation is carried out by thermally "insulating" the system from its surroundings. Temperature is the thermodynamic conjugate variable to entropy, thus the conjugate process would be an isothermal process in which the system is thermally "connected" to a constant-temperature heat bath.

Isentropic flow

An isentropic flow is a flow that is both adiabatic and reversible. That is, no heat is added to the flow, and no energy transformations occur due to friction or dissipative effects. For an isentropic flow of a perfect gas, several relations can be derived to define the pressure, density and temperature along a streamline.

Note that energy can be exchanged with the flow in an isentropic transformation, as long as it doesn't happen as heat exchange. An example of such an exchange would be an isentropic expansion or compression, which entails work done on or by the flow.

Derivation of the isentropic relations

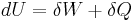

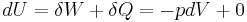

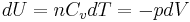

For a closed system, the total change in energy of a system is the sum of the work done and the heat added,

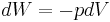

The reversible work done on a system by changing the volume is,

where  is the pressure and

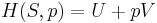

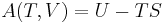

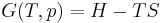

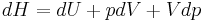

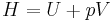

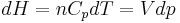

is the pressure and  is the volume. The change in enthalpy (

is the volume. The change in enthalpy ( ) is given by,

) is given by,

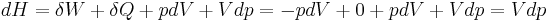

Then for a process which is both reversible and adiabatic (i.e. no heat transfer occurs),  , and so

, and so  . This leads to two important observations,

. This leads to two important observations,

, and

, and

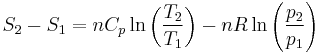

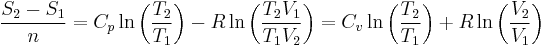

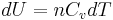

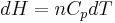

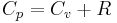

Next, a great deal can be computed for isentropic processes of an ideal gas. For any transformation of an ideal gas, it is always true that

, and

, and  .

.

Using the general results derived above for  and

and  , then

, then

, and

, and .

.

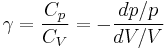

So for an ideal gas, the heat capacity ratio can be written as,

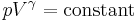

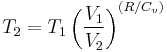

For an ideal gas  is constant. Hence on integrating the above equation, assuming a perfect gas, we get

is constant. Hence on integrating the above equation, assuming a perfect gas, we get

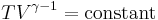

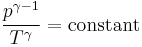

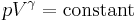

i.e.

i.e.

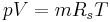

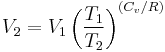

Using the equation of state for an ideal gas,  ,

,

also, for constant  (per mole),

(per mole),

and

and

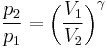

Thus for isentropic processes with an ideal gas,

or

or

Table of isentropic relations for an ideal gas

Derived from:

-

- Where:

= Pressure

= Pressure = Volume

= Volume = Ratio of specific heats =

= Ratio of specific heats =

= Temperature

= Temperature = Mass

= Mass = Gas constant for the specific gas =

= Gas constant for the specific gas =

= Universal gas constant

= Universal gas constant = Molecular weight of the specific gas

= Molecular weight of the specific gas = Density

= Density = Specific heat at constant pressure

= Specific heat at constant pressure = Specific heat at constant volume

= Specific heat at constant volume

- Where:

References

- Van Wylen, G.J. and Sonntag, R.E. (1965), Fundamentals of Classical Thermodynamics, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York. Library of Congress Calatog Card Number: 65-19470